Statements and control flow in python

Statements and control flow

Python's statements include:

- The assignment statement, using a single equals sign

= - The

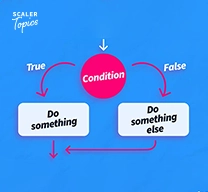

ifstatement, which conditionally executes a block of code, along withelseandelif(a contraction of else-if) - The

forstatement, which iterates over an iterable object, capturing each element to a local variable for use by the attached block - The

whilestatement, which executes a block of code as long as its condition is true - The

trystatement, which allows exceptions raised in its attached code block to be caught and handled byexceptclauses (or new syntaxexcept*in Python 3.11 for exception groups[86]); it also ensures that clean-up code in afinallyblock is always run regardless of how the block exits - The

raisestatement, used to raise a specified exception or re-raise a caught exception - The

classstatement, which executes a block of code and attaches its local namespace to a class, for use in object-oriented programming - The

defstatement, which defines a function or method - The

withstatement, which encloses a code block within a context manager (for example, acquiring a lock before it is run, then releasing the lock; or opening and closing a file), allowing resource-acquisition-is-initialization (RAII)-like behavior and replacing a common try/finally idiom[87] - The

breakstatement, which exits a loop - The

continuestatement, which skips the rest of the current iteration and continues with the next - The

delstatement, which removes a variable—deleting the reference from the name to the value, and producing an error if the variable is referred to before it is redefined - The

passstatement, serving as a NOP, syntactically needed to create an empty code block - The

assertstatement, used in debugging to check for conditions that should apply - The

yieldstatement, which returns a value from a generator function (and also an operator); used to implement coroutines - The

returnstatement, used to return a value from a function - The

importandfromstatements, used to import modules whose functions or variables can be used in the current program

The assignment statement (=) binds a name as a reference to a separate, dynamically allocated object. Variables may subsequently be rebound at any time to any object. In Python, a variable name is a generic reference holder without a fixed data type; however, it always refers to some object with a type. This is called dynamic typing—in contrast to statically-typed languages, where each variable may contain only a value of a certain type.

Python does not support tail call optimization or first-class continuations, and, according to Van Rossum, it never will.[88][89] However, better support for coroutine-like functionality is provided by extending Python's generators.[90] Before 2.5, generators were lazy iterators; data was passed unidirectionally out of the generator. From Python 2.5 on, it is possible to pass data back into a generator function; and from version 3.3, it can be passed through multiple stack levels.[91]

Comments

Post a Comment